Congreso Internacional “LLAMADO CONTRA LA DISCRIMINACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA DESDE EL PERÚ EN EL MARCO DEL DECENIO INTERNACIONAL DE LAS LENGUAS INDÍGENAS EN IBEROAMÉRICA”

O Instituto de Pesquisa de Lingüística Aplicada (CILA) da Faculdade de Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (UNMSM), juntamente com a Universidade de Antioquia (Colômbia), a Universidade de Jaén (Espanha), o Instituto Pedagógico Instituto de Caracas (Venezuela), o Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem da Universidade Estadual Campinas (Brasil), bem como instituições internacionais, a Diretoria de Línguas do Ministério da Cultura do Peru (Mincul), o Centro de Pesquisa Judicial do O Poder Judiciário do Peru (CIJ), os Serviços de Comunicação Intercultural (Servindi) e a Universidade Nacional do Altiplano (UAP), como instituições nacionais, apelam à comunidade universitária e aos interessados na luta contra a discriminação linguística (pesquisadores, professores, graduados , estudantes, usuários) para participar do Congresso Internacional “CHAMADA CONTRA A DISCRIMINAÇÃO LINGUÍSTICA DO PERU NO ÂMBITO DA DÉCADA INTERNACIONAL DE LÍNGUAS INDÍGENAS NA IBERO AMÉRICA”, evento que será realizado semipresencialmente na quarta-feira 20, quarta-feira 13, Quinta-feira, 14 e sexta-feira, 15 de dezembro.

No âmbito da DÉCADA INTERNACIONAL DAS LÍNGUAS INDÍGENAS NA IBERO-AMÉRICA, investigadores das disciplinas de Linguística e de diversas disciplinas preocupam-se com o desenvolvimento linguístico, razão pela qual se reúnem neste Congresso Internacional para debater e reflectir sobre o uso, a sobrevivência e a revitalização das línguas face à discriminação linguística.

Neste século 21 estima-se que mais de 3.000 línguas irão desaparecer. No Peru existem mais de 40 línguas nativas, que estão em perigo de extinção, incluindo Cocama, Taushiro e Jacaru. O Instituto de Pesquisa de Linguística Aplicada (CILA) incentiva o uso, a revitalização e a promoção das línguas nativas, uma vez que seus falantes têm todos os direitos linguísticos dos demais falantes para sua sobrevivência e desenvolvimento social e de sua comunidade, que luta contra a discriminação linguística e racial que existe no mundo. Por isso é necessário realizar um congresso que convoque a luta pelas línguas indígenas no Peru, na América Latina e no mundo.

Link com Google Meet:

https://meet.google.com/xjv-dfvm-pbm

Rosangela Morello, coordenadora do Instituto de Investigação e Desenvolvimento em Política Linguística (IPOL), participará no dia 13 de dezembro (quarta-feira) com a apresentação “A necessidade de políticas de reparação à repressão e ao preconceito linguístico” com a moderação de Andrés Napuri.

O Brasil, país bilíngue desde 2005 (português/Língua Brasileira de Sinais – LIBRAS), é muito rico em diversidade linguística. Com cerca de 300 línguas, está entre os oito países com maior número de línguas no mundo, no entanto o Estado Brasileiro constituiu-se como Estado Nacional, tendo estabelecido uma equivalência entre o conceito de nação e a unidade da língua portuguesa. Nesse sentido, proibiu e exterminou línguas faladas por centenas de milhares de indígenas, africanos, europeus, imigrantes e surdos. Esse processo conduziu à exclusão da cidadania e do acesso a políticas públicas de significativa parcela da população brasileira.

Esse fato, por muitos desconhecidos, justifica a Nota Técnica Conscientização do direito humano à diversidade linguística e formas de compensação pela história de repressão linguística no Brasil desde o início do processo de colonização, assinada pelo IPOL Instituto de Investigação e Desenvolvimento em Políticas Linguísticas, Defensoria Pública da União (DPU) e Universidade de Brasília (UNB) e publicada em 14 de setembro de 2021. Com o objetivo promover a conscientização e a promoção do direito humano à diversidade linguística para todos os brasileiros de todas as línguas, a Nota estabelece uma nova frente de reivindicação dos direitos linguísticos no Brasil na medida em que insta o Estado, em todas as suas instâncias representativas e instituições vinculadas, a promover políticas de reparação ao extermínio e repressão históricos de línguas em território brasileiro. Na exposição, explicitaremos brevemente o contexto de elaboração desta nota, alguns acontecimentos históricos que a justificam e exploraremos suas potencialidades como instrumento de reivindicação de direitos linguísticos e de reconhecimento e promoção das línguas e de seus falantes.

Saiba mais puxando a rede do IPOL!

. Leia a NOTA TÉCNICA No 8 – DPGU/DNDH – Conscientização do direito humano à diversidade linguística e formas de compensação pela história de repressão linguística no Brasil desde o início do processo de colonização

. Brasileiro fala português: Monolingüismo e Preconceito Lingüístico, por Gilvan Müller de Oliveira https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000161167

Ministra dos Povos Indígenas formaliza adesão do Brasil ao Instituto Iberoamericano de Línguas Indígenas (IIALI)

Na última terça-feira, dia 21 de novembro de 2023, a ministra dos Povos Indígenas, Sonia Guajajara, assinou um ofício solicitando à Agência Brasileira de Cooperação (ABC) a adesão do Brasil ao Instituto Iberoamericano de Línguas Indígenas (IIbeLI). A formalização deste pedido visa preservar e revitalizar o patrimônio linguístico e cultural da América Latina e do Caribe, conforme aprovado na Cúpula Iberoamericana de fevereiro de 2022.

Na última terça-feira, dia 21 de novembro de 2023, a ministra dos Povos Indígenas, Sonia Guajajara, assinou um ofício solicitando à Agência Brasileira de Cooperação (ABC) a adesão do Brasil ao Instituto Iberoamericano de Línguas Indígenas (IIbeLI). A formalização deste pedido visa preservar e revitalizar o patrimônio linguístico e cultural da América Latina e do Caribe, conforme aprovado na Cúpula Iberoamericana de fevereiro de 2022.

A reunião da Organização Iberoamericana, agendada para o dia 27 de novembro, será palco para a ABC formalizar a adesão brasileira ao IIbeLI. Esta é uma iniciativa crucial para a preservação das cerca de 550 línguas na região, sendo um terço delas ameaçadas de extinção, é uma entrega concreta do Ministério dos Povos Indígenas durante sua liderança na Presidência Pro-tempore do Mercosul.

A adesão ao IIbeLI é estratégica para o reposicionamento do Brasil no cenário regional, destacando o protagonismo indígena. Durante a Reunião de Autoridades sobre Povos Indígenas do Mercosul (RAPIM), realizada em Brasília em 16 de novembro, a decisão brasileira já foi comunicada ao Vice-Presidente da Bolívia, David Choquehuanca, país sede do Instituto e um de seus maiores apoiadores.

Essa iniciativa ganha ainda mais relevância no contexto da Década Internacional das Línguas Indígenas da UNESCO, à medida que os países são chamados à ação para apoiar, promover e revitalizar as línguas indígenas. Além disso, a adesão fortalecerá a parceria com o FILAC (Fundo para o Desenvolvimento dos Povos Indígenas da América Latina e Caribe), possibilitando ações conjuntas em eventos como o Fórum Permanente sobre Questões Indígenas da ONU e a participação indígena na COP30 do Clima, em 2025, em Belém.

A medida alinha-se à intenção do presidente Lula de fortalecer a integração regional, especialmente no âmbito do Tratado de Cooperação Amazônica (TCA), considerando a concentração significativa das línguas indígenas na região.

Por fim, a adesão ao Instituto Iberamericano de Línguas Indígenas vem ao encontro das ações do Ministério dos Povos Indígenas que, por meio de seu Departamento de Línguas e Memórias Indígenas, chefiado pelo professor Eliel Benites. O Departamento apresentou este ano, no âmbito da RAPIM, o Plano de Ação para a Década Internacional das Línguas Indígenas no Brasil, o qual apresenta em detalhes os princípios, objetivos e, principalmente, as ações conduzidas à frente das políticas linguísticas no Brasil, tudo formulado com protagonismo indígena e intensos diálogos com instituições governamentais e não-governamentais especializadas na temática.

IIALI – O que é?

O Instituto Ibero-Americano de Línguas Indígenas é uma iniciativa para revitalizar as línguas indígenas

O Instituto Ibero-Americano de Línguas Indígenas (IIALI) tem sua origem em uma decisão da Cúpula Ibero-Americana de Chefes de Estado e de Governo, realizada em Montevidéu e Antígua-Guatemala em 2006 e 2018, respectivamente. Na XXVII Cúpula Ibero-Americana, realizada em Andorra em 2021, o instituto foi aprovado como uma iniciativa ibero-americana para enfrentar as ameaças às línguas indígenas, especialmente as ameaçadas de extinção, bem como para promover seu uso, revitalizar, fomentar e desenvolver as mesmas.

Esta iniciativa busca aumentar a consciência da situação das línguas indígenas e dos direitos culturais e linguísticos dos povos indígenas; promover a transmissão, uso, aprendizagem e revitalização das línguas indígenas; prestar assistência técnica na formulação e implementação de políticas linguísticas e culturais para os povos indígenas; e facilitar a tomada de decisão informada sobre o uso e vitalidade das línguas indígenas.

O instituto adota, entre outros, os princípios da Convenção 169 da OIT, a Declaração da ONU sobre os Direitos dos Povos Indígenas e a Declaração Los Pinos-Chapoltepek, adotada no evento de alto nível convocado pela UNESCO e pelo Governo do México em 2020, sob o lema “Nada sem nós”, que reconhece a importância das línguas indígenas para a coesão e inclusão social, direitos culturais, saúde e justiça.

A responsabilidade pela criação do Instituto foi confiada na XXVI Cúpula Ibero-Americana de Chefes de Estado e de Governo à Organização de Estados Ibero-Americanos para a Ciência e a Cultura (OEI), à Secretaria-Geral Ibero-Americana (SEGIB) e ao Fundo para o Desenvolvimento dos Povos Indígenas da América Latina e do Caribe (FILAC).

El IIALI tiene como objetivo general fomentar el uso, la conservación y el desarrollo de las lenguas indígenas habladas en América Latina y el Caribe, apoyando a las sociedades indígenas y a los Estados en el ejercicio de los derechos culturales y lingüísticos, objetivo que se logrará con la creación de un Instituto Iberoamericano de Lenguas Indígenas. Para ello, se busca:

- Concienciar sobre sobre la situación de las lenguas indígenas y los derechos culturales y lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas, así como lograr:

- Que la sociedad global considere al IIALI como la piedra angular del Decenio Internacional de las Lenguas Indígenas en América Latina y el Caribe.

- Que la sociedad latinoamericana muestre mayor conocimiento y consciencia sobre la situación de vulnerabilidad y los riesgos que amenazan a los idiomas indígenas.

- Fomentar la transición, uso, aprendizaje y revitalización de los idiomas indígenas, a través de ello se busca:

- Que se retome la transmisión intergeneracional de los idiomas indígenas por las familias indígenas.

- Se cree un sistema de apoyos para iniciativas endógenas de recuperación y revitalización de los idiomas originarios, en áreas rurales y urbanas.

- Sean aplicadas iniciativas gubernamentales en favor de las lenguas indígenas en consulta con las organizaciones indígenas y las comunidades de hablantes.

- Formular e implementar políticas lingüísticas y culturales para y con los pueblos indígenas, también es parte de los objetivos del IIALI, para ello se pretende:

- Que sean fortalecidos técnicamente las Secretarías, institutos o academias oficiales de idiomas originarios y políticas lingüísticas y con actuación en los niveles macro, meso y micro.

- Tener un Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Lenguas Indígenas en funcionamiento, con bases de datos cuantitativos y cualitativos sobre la situación de los idiomas indígenas. (https://www.iiali.org/objetivos-del-iiali/)

Saiba mais puxando. rede IPOL:

. A criação do Instituto: http://ipol.org.br/tag/instituto-ibero-americano-de-linguas-indigenas-iiali/

. A criação do Instituto Ibero-Americano de Línguas Indígenas (IIALI): https://www.segib.org/pt-br/programa/iniciativa-instituto-iberoamericano-de-lenguas-indigenas-iiali/

António Branco: “Não sou utópico nem catastrofista. Todas as tecnologias têm um duplo uso”

(Por Paula Sofia Luz, Diário de Noticias – Lisboa –

António Branco. Foi pioneiro ao trabalhar o tema da inteligência artificial, é primeiro coautor do livro branco sobre a língua portuguesa e a IA e criador do Albertina.pt, primeiro modelo aberto para a língua portuguesa.

Como e quando começou esse seu interesse pela temática da inteligência artificial (IA)?

Foi em novembro de 1987. Eu tinha acabado a licenciatura e envolvi-me num grande projeto para desenvolver tradução automática entre todas as línguas da União Europeia.

Passaram muitos anos até que a temática se democratizasse, exatamente há um ano…

Sim, não tenho dúvida de que isso só aconteceu em novembro de 2022. Parte do meu trabalho consiste na divulgação, e ao longo dos anos tenho-me empenhado bastante nisso, nomeadamente no livro de que sou coautor, publicado em 2012, o livro branco sobre a língua portuguesa na era digital. Que foi muito importante, mas com pouco eco. Há um ano, com a disponibilização do ChatGPT, nós – que por vezes éramos considerados uns certos lunáticos, ou, no mínimo, pessoas com uns interesses específicos muito estranhos – de repente passámos a ser glorificados.

Está mais do lado dos que consideram a IA uma oportunidade do que como uma ameaça?

Nem uma coisa nem outra. Eu estou do lado daqueles que sensatamente, olhando para todas as tecnologias (e esta não vai ser exceção), sabem que elas têm um duplo uso. Tem usos benéficos e outros prejudiciais. Portanto, não sou utópico nem catastrofista.

O desenvolvimento de grandes modelos neuronais de IA generativa para a língua portuguesa ainda agora começou (Fonte Unsplash+ com Getty Images)

Acredita que a IA, bem usada, é uma ferramenta poderosa? Nomeadamente para melhorar muitas áreas?

Sem dúvida. Já em 1987 era um sonho imenso, fantástico, imaginar que eu podia contribuir para um dia deixar de haver barreiras de comunicação linguística. Era mesmo a ideia de mudar o mundo: todas as pessoas a falar umas com as outras, mesmo só conhecendo a sua língua materna. E esse sonho está agora a concretizar-se. Esse é um exemplo que acho extraordinariamente benéfico. Nós vamos poder falar com qualquer outro habitante que fale qualquer outra das sete mil línguas existentes no planeta Terra.

Neste ano que passou, como é que lhe parece que a sociedade portuguesa tem vindo a lidar com esta nova realidade da IA, cada vez mais presente na vida de todos?

A sociedade portuguesa tem várias esferas, dimensões e atores. Se falarmos, por exemplo, na comunicação social, julgo que a reação foi muito apropriada. Tem sido dado um destaque adequado à verdadeira importância desta tecnologia. Mas se falarmos no domínio governamental, das políticas públicas, a minha opinião é a oposta. Tem sido um vazio, até comparativamente à vizinha Espanha. Eles têm um PRR como nós, mas estabeleceram um capítulo de financiamento de mil milhões de euros, durante cinco anos, para aplicar na tecnologia da língua espanhola. E nós, em Portugal, destinámos zero. Mas se formos para outras geografias, como os Estados Unidos da América, estão destinados dezenas de milhares de milhões. Porque o país, para preservar a sua soberania, não se deixa ficar apenas na mão de organizações privadas. E nós, em Portugal, se nada for feito, continuaremos a subtrair a nossa soberania linguística e digital.

Leia a matéria na fonte: https://www.dn.pt/sociedade/antonio-branco-nao-so-utopico-nem-catastrofista-todas-as-tecnologias-tem-um-duplo-uso-17361996.html

Saiba mais sobre Albertina, primeiro modelo aberto para a língua portuguesa.pt puxando a rede do IPOL:

. Já conhece o Albertina PT?

https://ciencias.ulisboa.pt/pt/noticia/22-05-2023/já-conhece-o-albertina-pt?page=1

. Lançada a primeira Inteligência Artificial que gera textos em português sobre qualquer tema. Chama-se Albertina

http://www.di.fc.ul.pt/~ahb/images/AlbertinaExpressoMaio2023.pdf

. Língua portuguesa entra na era da IA

. “Há um risco de hiperconcentração dos grandes modelos Inteligência Artificial na Microsoft e na Google”, avisa António Branco

. Conheça a publicação de 2012 “Livro Branco sobre a Língua Portuguesa na Era Digital”

http://metanet4u.weebly.com/livro-branco-a-lingua-portuguesa-na-era-digital.html

Este Livro Branco, sobre a língua portuguesa na era digital, faz parte de uma coleção que promove o conhecimento sobre a tecnologia da linguagem e o seu potencial. É dirigido a um público o mais vasto possível, não especializado nestas matérias, incluindo comunidades linguísticas, jornalistas, políticos ou docentes, entre muitos outros.

O livro procura disponibilizar uma análise do estado de desenvolvimento da tecnologia da linguagem para a língua portuguesa, assim como das perspetivas que se oferecem, e das ações necessárias, para a consolidação do português como língua de comunicação internacional com projeção global na era digital no quadro desta tecnologia emergente.

Abra o link abaixo para alcançar a versão ebook da publicação:

http://metanet4u.eu/wbooks/portuguese.pdf

. Saiba mais a Coleção Livros Brancos da META-NET

http://www.meta-net.eu/whitepapers/overview-pt

As Línguas Europeias na Era Digital

Objetivos e Dimensão

A META-NET, uma rede de excelência que consiste em 60 centros de pesquisa de 34 países, dedica-se à construção de bases tecnológicas da sociedade de informação multilingue europeia.

A META-NET está a construir a META, uma Aliança Tecnológica Europeia Multilingue. Os benefícios conferidos pelas Tecnologias da Linguagem diferem de língua para língua, tal como as ações que precisam de ser tomadas dentro da META-NET, dependendo de diversos fatores, tais como a complexidade da língua em questão, a densidade da sua comunidade e a existência de centros de pesquisa ativos nesta área.

A Coleção Livros Brancos da META-NET «Línguas na Sociedade de Informação Europeia» descreve o estado de cada língua europeia, respeitando as Tecnologias da Linguagem, explicando os riscos e as oportunidades mais urgentes. A coleção abrange todas as línguas oficiais europeias e muitas outras faladas noutros locais do Velho Continente. Não obstante a publicação de diversos estudos científicos acerca de determinados aspetos sobre as línguas e a tecnologia ao longo dos últimos anos, não existe uma fonte literária exaustiva a tomar uma posição apresentando os principais desafios e descobertas para cada língua. A Coleção Livros Brancos da META-NET preencherá esta lacuna.

31 Volumes cobrem 30 Línguas Europeias

Basco, Búlgaro, Catalão, Croata, Checo, Dinamarquês, Holandês, Inglês, Estoniano, Finlandês, Francês, Galego, Alemão, Grego, Húngaro, Islandês, Irlandês, Italiano, Letão, Lituano, Maltês, Norueguês (antigo), Norueguês (moderno), Polaco, Português, Romeno, Sérvio, Eslovaco, Esloveno, Espanhol, Sueco.

Em Resumo

“Inventário da Língua Pomerana (ILP)” está disponível em formato e-book. Errata

Errata: um novo link para acesso da publicação está disponível na postagem:

“Inventário da Língua Pomerana (ILP)” está disponível em formato e-book.

“Inventário da Língua Pomerana (ILP)” está disponível em formato e-book.

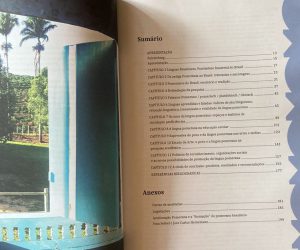

O projeto Inventário da Língua Pomerana (ILP), uma pesquisa coordenada pelo IPOL para conhecer a situação atual da língua pomerana presente em alguns estados do Brasil, concluído em 2022, após distribuir exemplares pelos estados onde foi realizada a pesquisa, disponibiliza agora a publicação em formato e-book o livro Inventário da Língua Pomerana (língua brasileira de imigração) para alcançar maior número de falantes da língua, interessados e pesquisadores.

Rosângela Morello, coordenadora do IPOL e organizadora do livro juntamente com Mariela Silveira, destaca que a ideia de realizar o Inventário da Língua Pomerana: língua brasileira de imigração (ILP) surgiu muito antes da publicação do Decreto 7.387 de 2010, que instituiu a política do Inventário Nacional da Diversidade Linguística (INDL). Relembra que já em 2006, durante o Seminário de Criação do Livro de Registro das Línguas, promovido pelo IPHAN e IPOL, na Câmara dos Deputados, em Brasília, entre os depoimentos emocionados de falantes e representantes de várias comunidades linguísticas brasileiras estavam representantes do povo pomerano do Espírito Santo como Sintia Bausen. Foi a partir dali que se iniciou uma parceria muito produtiva entre o IPOL e as comunidades pomeranas capixabas, gerando condições para a realização conjunta de várias políticas linguísticas, entre as quais se destacam i) as audiências para a cooficialização da língua pomerana em Santa Maria de Jetibá, ii) a construção de um parecer jurídico para ampa- rar a legislação municipal sobre a cooficialização do Pomerano, uma língua de descendentes de imigrantes, de estatuto distinto daquela das indígenas cooficializadas em São Gabriel da Cachoeira, cuja autonomia se amparava também na Constituição Federal de 1988, e iii) o primeiro censo linguístico municipal no mesmo município de Santa Maria de Jetibá.

O próximo passo foi possível através Conselho Gestor do Fundo de Defesa dos Direitos Difusos (CFDD) que abriu em 2015 um edital para fomento de inventários e a imediata a articulação para construir uma proposta para a língua pomerana, finalmente contratada em 2017.

O Inventário da Língua Pomerana, língua brasileira de imigração (ILP) foi então concebido e realizado como uma ação para o reconhecimento dessa língua como Referência Cultural Brasileira para resguardar e promover as comunidades linguísticas e suas referências culturais e identitárias de acordo com a linha instituída pelo IPHAN e a Política do Inventário Nacional da Diversidade Linguística do Brasil, instituída pelo Decreto Federal n. 7.387, de 9/12/2010.

O projeto foi realizado com os moldes do Guia INDL (IPHAN, 2015), abrangendo a sistematização de conhecimentos sobre a denominação e classificação da língua, sua situação sócio-histórica, âmbitos de usos e circulação, registro audiovisual, dados demolinguísticos e sua situação nas práticas de ensino e pesquisa. O resultado Inventário oferece uma visão abrangente e articulada dos usos e vitalidade dessa língua nas comunidades de referência abordadas na pesquisa.

Com esta publicação os resultados da pesquisa ficam disponíveis para acesso gratuito, como prevê a Política do INDL, garantindo a continuidade de ações para a promoção dessa língua na educação, nas artes, na cultura, na ciência e tecnologia e nos direitos dos cidadãos. Agradecemos a colaboração de Sintia Bausen, Carmo Thum, Edineia Koeler, Erineu Foerste, Giales Rutz, Jandira Dettmann, Lilia Stein, entre muitos outros que tornaram possível e desejamos que o povo pomerano usufrua desta conquista.

Acesse o novo link para a publicação: Inventário da Língua Pomerana

Inteligência artificial e a preservação das línguas indígenas

IA ajudará a preservar línguas indígenas, em projeto de USP e IBM

Um projeto conjunto da USP, por meio do Centro de Inteligência Artificial (C4AI) e da IBM Research, está sendo desenvolvido com o uso da inteligência artificial (IA) para preservar e fortalecer as línguas indígenas brasileiras. Ainda em fase inicial, o objetivo é criar e desenvolver ferramentas com suporte da tecnologia que auxiliem a documentação, a preservação e o uso desses idiomas, em parceria com as comunidades de povos indígenas.

A partir de um contato pessoal que o vice-diretor do C4AI, Claudio Pinhanez, tinha com a comunidade indígena da Terra Indígena Tenonde Porã, no sul da cidade de São Paulo, a ideia do projeto foi iniciada há cerca de um ano, dentro da IBM Research. O professor, um dos líderes do projeto junto com a professora Luciana Storto, da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas (FFLCH) da USP, conta que viram na comunidade um lugar interessante para terem esse diálogo com a tecnologia.

“Como é que a gente mantém vivas essas línguas? No Brasil, a gente tem em torno de 200 línguas faladas hoje, e metade tem chance de desaparecer nos próximos 20 a 50 anos. Cada língua que se perde é como se tratorasse um sítio arqueológico. É a imagem que tem que fazer. Imagina que você tem um sítio arqueológico onde existe uma cultura e alguém passa o trator lá em cima. Isso é perder uma língua, é perder um jeito de pensar, um jeito de ver o mundo, o conhecimento sobre o mundo etc”, questiona Pinhanez.

Ele afirma que a língua morre quando os jovens param de falá-la. Esse projeto consegue ajudar, juntamente com a tecnologia, as línguas indígenas a se fortalecerem, a serem mais faladas, e pode ajudar linguistas a documentar aquelas que já estão em um processo mais avançado de extinção de uma maneira mais eficiente.

Siga a leitura na fonte: https://www.mobiletime.com.br/noticias/13/07/2023/projeto-da-usp-e-ibm-usa-ia-para-fortalecer-linguas-indigenas/

____________________

Saiba mais sobre IA puxando a Rede:

Inteligência Artificial nas Ondas do Rádio: IA e a preservação de Línguas Indígenas

Ouça o Prof. Marcelo Finger, um dos principais nomes em IA no País, discorrendo sobre o tema da preservaç˜åo das línguas indígenas

Marcelo Finger fala sobre IA para um público curioso e interessado

Marcelo Finger fala sobre IA para um público curioso e interessado

A preservação de línguas indígenas através da tecnologia

USP desenvolve projetos em linguística e alfabetização baseados em IA

https://www.mobiletime.com.br/noticias/02/08/2023/usp-desenvolve-projetos-baseados-em-ia/