Cacica Tônkyre e as línguas cantadas: entre rios e palavras

José Bessa Freire

E à noite nas tabas, se alguém duvidava / do que ele contava / tornava prudente: “Meninos, eu vi!” (Gonçalves Dias. I-Juca-Pirama, 1851)

– Minha filha, se eles invadem a aldeia e começam a matar teus irmãos, foge. Foge, minha filha. Foge!

Este conselho do cacique Payaré dado na língua Jê-Timbira à sua filha pequena Tônkyre Akrãtikatêjê, a primeira cacica do povo Gavião hoje com 53 anos, parece desconcertante na boca do valente guerreiro, cuja vida foi marcada por coragem e solidariedade. Estava ele se acovardando? Ou queria manter viva a filha, tal qual o literário guerreiro tupi I-Juca-Pirama preso pelos Timbira, que chorou diante da morte para salvar seu pai cego? Nada disso. Na sequência, Payaré completou:

– Escapa, minha filha, porque alguém tem de sobreviver para contar o que testemunhou com seus próprios olhos.

A filha, que depois substituiria o pai, sobreviveu e seguiu a recomendação sobre a necessidade de ocupar outra trincheira de combate: a da luta pela memória, sempre controlada pelo inimigo, que a manipula e distorce. Não era uma fuga, mas a escolha do campo de batalha, que requer combatentes do lado de cá, como no poema épico de Gonçalves Dias, de dez cantos e 484 versos, no qual o “velho Timbira, coberto de glória, guardou a memória” daquilo que presenciara.

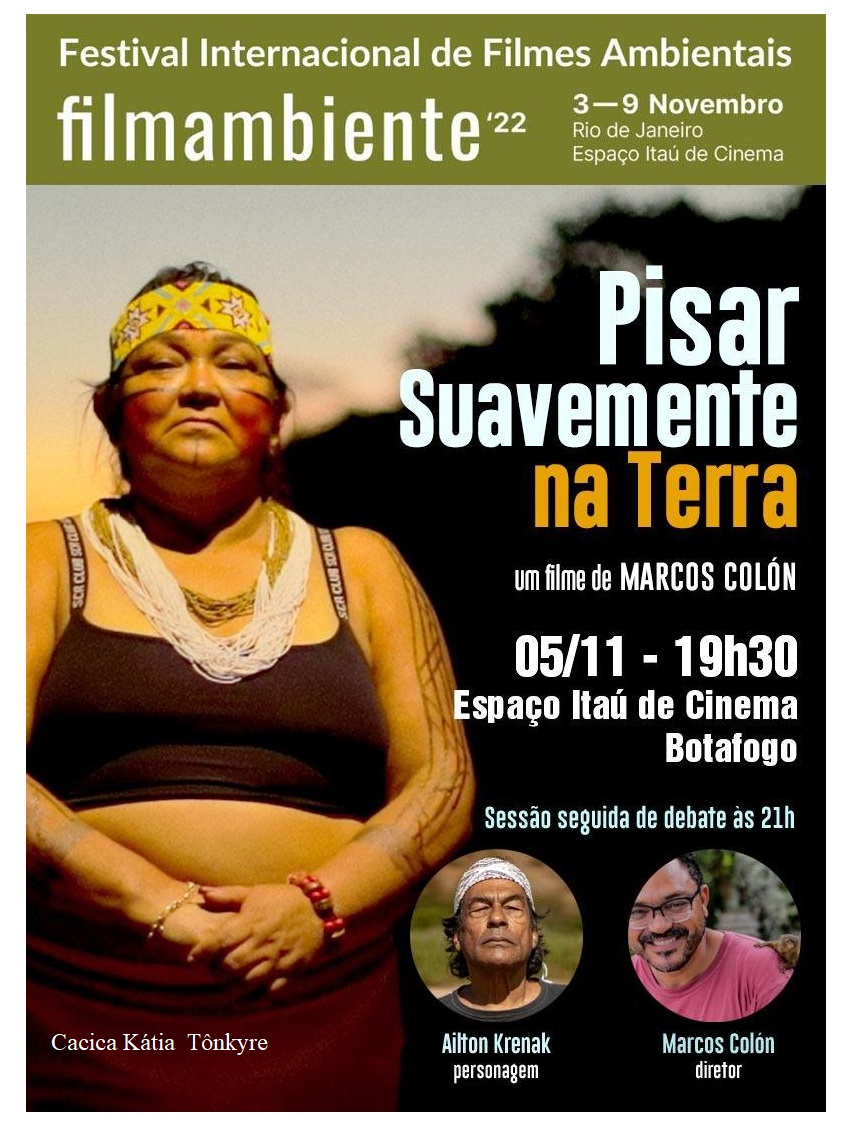

A luta pela memória passou pela recuperação da sua identidade e de seu nome indígena recusado pelo Cartório, que a registrou como Kátia – assim é hoje conhecida no Brasil. A conversa com o pai, aqui contada do meu jeito, está no filme “Pisar Suavemente na Terra” de Marcos Colón, lançado no Rio, sábado (5). Mas Kátia Tônkyre aparece ainda em outros dois filmes: “Entre Rios e Palavras: as línguas indígenas no Pará em 2021”, de Maurício Correia e indiretamente em Segredos do Putumayo, de Aurélio Michiles, os três filmes unidos pela temática da memória.

Pisar de leve na terra

O combate pela preservação da memória, das línguas e do território atravessa toda a Amazônia indígena assaltada por empreendimentos modernizantes, que falam em nome do progresso, numa destruição planejada pela “economia do desastre” – segundo Ailton Krenak, um dos narradores do Pisar Suavemente na Terra. “Só trazem destruição, drogas, prostituição” diz o cacique Manoel Munduruku e criam “miséria, pobreza, contaminação, corrupção” nas palavras do Kokama José Manuyana.

As imagens revelam a área desmatada da mina de bauxita da Alcoa, em Juriti (PA), a rodovia Br-222, a estrada de ferro Carajás que corta a aldeia da mesma forma que os linhões de transmissão elétrica, o trem noturno que desperta moradores e espanta animais, o embarque da soja em Santarém, as hidrelétricas de Belo Monte e Tucuruí, o garimpo do rio Tapajós que mata a vida aquática, a ação devastadora de madeireiros e até o desfile de urubus entre as palafitas de Iquitos, no Peru. A Amazônia está ferida de morte.

Como resistir num contexto em que a economia só existe se o desastre acontece, como ocorreu com mineração na Terra Indígena Krenak em área do Rio Doce narrada por Ailton?

A câmara acompanha o professor Kokama na Amazônia peruana, de onde se desloca para as aldeias do Pará. Em uma delas está o cacique Manoel Munduruku. Na outra Kátia Tônkyre, com sua assombrosa lucidez, relembra quando, aos 9 anos, presenciou o cerco à sua família, em Tucuruí, nos anos 1980, e três jagunços tentaram degolar seu pai. Mas o documentário registra também a resistência. No debate que se seguiu até às 23h00 com Ailton Krenak, Marcos Colón declarou:

– A Amazônia é geralmente pensada como mercadoria, como objeto de exploração. Mas devemos pensar a Pan-Amazônia a partir dos seus povos, do que é importante para eles: os modos de sobrevivência, a água, a floresta, a biodiversidade, as culturas locais porque, como disse Ailton Krenak “a gente só existe porque a terra deixa a gente viver. É a mãe terra que nos dá a vida. É preciso pisar suavemente na terra”.

Entre rios e palavras cantadas

Katia Tônkyre protagoniza também o outro filme Entre rios e palavras, onde dialoga sobre a história do Nheengatu e das línguas na Amazônia com vários indígenas, entre eles Bewari Tembé, Muraygawa Assurini, Márcia Kambeba e Dayana Borari. O filme exibido no V Colóquio Internacional Mídia e Discurso na Amazônia (DCIMA), em Belém, nesta quinta (10), foi seguido da mesa A Revolução Linguística no Baixo Tapajós com falas de Sâmela Ramos, Luana Kumaruara, Raquel Tupinambá e Vera Arapium.

O tema do evento “Outros Possíveis” foi na mesma direção do “Pisar suavemente na terra”. Seu objetivo foi visibilizar e fortalecer formas de vida diferentes das normas ditadas pelo sistema capitalista, com propostas para desconstruir a colonialidade, consciente de que “o planeta não é uma propriedade privada do homem”, que existem muitas outras linguagens além da palavra e que é necessário ver o mundo a partir de outro lugar.

A revolução linguística feita pelos Grupos de Consciência Indígena do Tapajós (GCI) recupera a memória e os processos próprios de aprendizagem do Nheengatu e de outras línguas indígenas duramente reprimidas. Kátia Tônkyre fala da preocupação do seu pai para que fosse alfabetizada em sua língua e resume a pedagogia Akrãtikatêjê, explicando como os ensinamentos são passados por meio de canções, com lições aprendidas na vivência diária. A língua é falada e, sobretudo, cantada, antes de ser escrita.

– É a aprendizagem de como a gente inventa as músicas, como elas podem ser cantadas para entender a época de plantar, de conservar as sementes, da importância de guardar as músicas através das brincadeiras, do dia a dia, do tempo. Nossas músicas cantam os animais, o tempo, a madrugada, a noite, o cotidiano, o caminhar. Nós temos músicas da cabeça da onça, do peixe, da anta, da guariba, de cada animal, que são repassadas como mensagens, um recado através da cantiga.

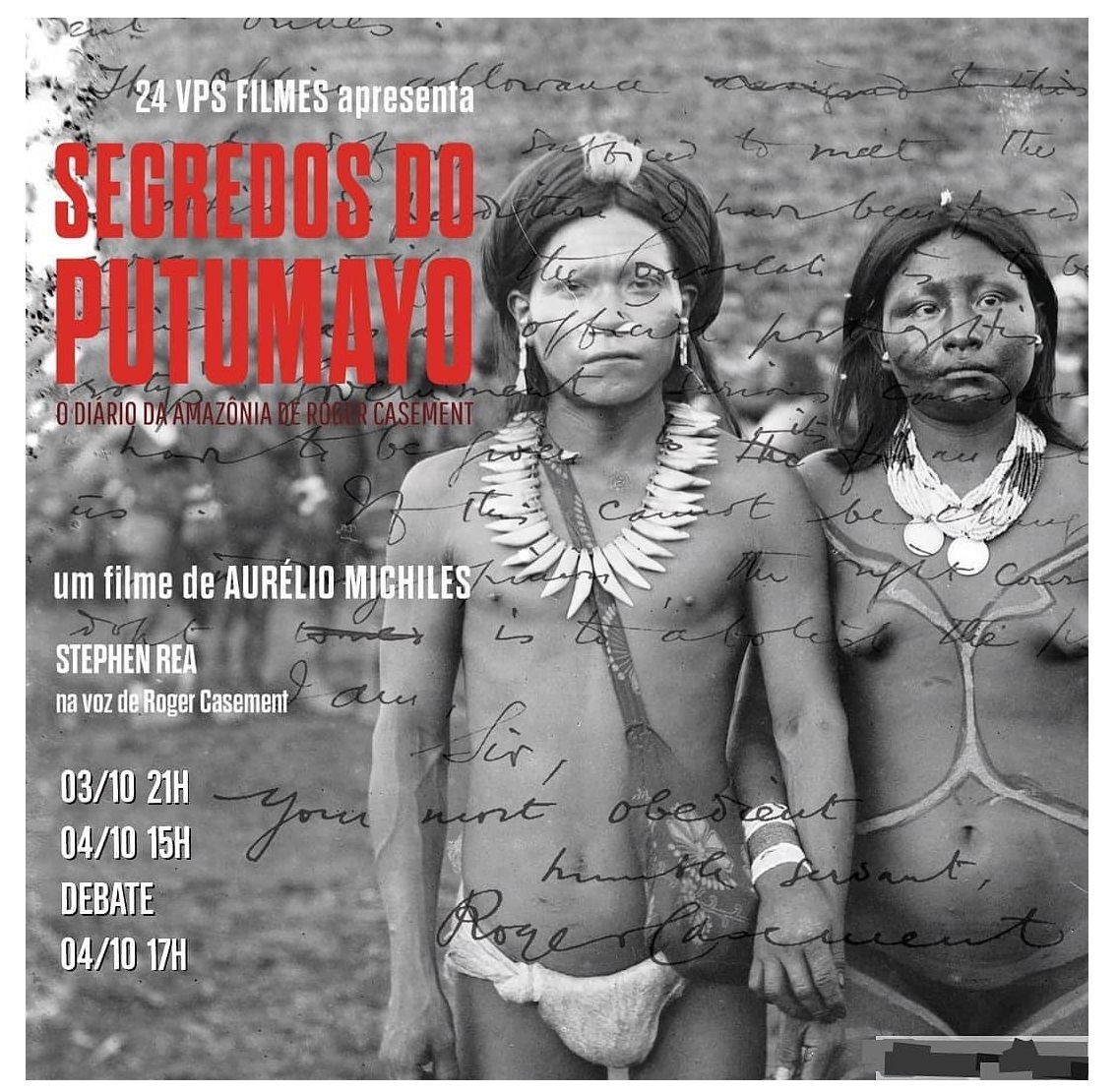

Segredos do Putumayo

Embora os Gaviões Akrãtikatêjê não tenham presença física n0 longa-metragem Segredos do Putumayo, a preocupação pela memória foi discutida pelo diretor Aurélio Michiles e por Wanda Uitoto na quinta (27/10), quando o filme foi exibido no seminário “Darcy Ribeiro: pensamento humanista em tempos de barbárie” organizado pela Casa de Oswaldo Cruz.

O extermínio de mais de 30 mil indígenas no rio Putumayo aparece em todo seu horror no documentário, que recupera o diário do diplomata e nacionalista irlandês a serviço da Coroa Britânica, Roger Casement (1864-1916), cônsul no Brasil. Ele foi encarregado de investigar, em 1910, as condições de trabalho da Peruvian Amazon Company, financiada pela Bolsa de Londres, que escravizava indígenas nos seringais.

As informações do Diário de Casement, julgado e condenado à morte na forca pelo crime de “traição, sabotagem e espionagem contra o Reino”, são complementadas por imagens de Silvino Santos No País das Amazonas (1922), depoimentos, entre outros, do historiador Angus Mitchell, do escritor Milton Hatoum e de indígenas dos povos Uitoto, Bora, Okaina e Muinames, habitantes de La Chorera (Colômbia), depositários da memória e da documentação oral. Lá Michiles entrevistou uma igualmente brilhante Kátia local.

A exibição dos três filmes que tive a sorte de ver antecedem o 1º Festival de Cinema e Cultura Indígena (FeCCI) a ser realizado em Brasília de 2 a 11 de dezembro, com programação de longas-metragens de temática indígena e ambiental focada no tema central: “Como você cuida da sua aldeia?” e com indicações de caminhos sobre outras formas de viver no mundo. Já sabemos como os Gaviáo- Akrãtikatêjê cuidam de sua aldeia, onde a cacica Kátia vive com sua sabedoria. Meninas, ela viu. E todo mundo também agora pode ver, graças ao testemunho dela.

- Pisar suavemente na terra. Direção de Marcos Colón, filmado no Brasil, Colômbia e Peru e vencedor do Prêmio de Melhor Fotografia no Festival Filmambiente 2022. Com Kátia Akrãtikatêjê, Manoel Munduruku, José Manuyama e Ailton Krenak. 83 minutos.

- Entre rios e palavras: as línguas indígenas no Pará, direção e montagem de Mauricio Neves Correia. Produção Ivânia Neves GEDAI. Elícia Tupinambá – Se anama (versão de Florêncio Vaz). 76 minutos

- Segredos do Putumayo dirigido por Aurélio Michiles e filmado na Amazônia brasileira e colombiana, inspirado no “Diário da Amazônia” de Roger Casement. Fotografia de André Lorenz Michiles. 83 minutos

Comunidades e povos tradicionais é tema da redação do Enem 2022

Marcelo Casal Jr – Agência Brasil

Para especialistas, exame apresentou tema “eternamente contemporâneo”

O tema da redação do Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (Enem) de 2022 é “Desafios para a valorização de comunidades e povos tradicionais no Brasil”, conforme divulgado pelo Ministério da Educação. O tema vale para as duas versões do Enem: impressa e em computador.

Especialista em redação e mestre em literatura indígena pela Universidade de Brasília (UnB), a professora Ana Clara Oliveira avalia que o tema deste ano segue as tradições do Enem, com “uma pegada social muito forte” e tratando de um recorte muito específico: os povos e comunidades tradicionais.

“Mais do que se restringir a esses povos, o tema abrange os desafios que o resto da sociedade tem para valorizá-los”, disse à Agência Brasil a professora do cursinho de redação online Corujando.

Eternamente contemporâneo

“Como sempre, o Enem foi muito bem na escolha temática”, acrescentou a professora formada em Letras pela UnB. Segundo ela, trata-se de um tema “eternamente contemporâneo”, mas que ganha ainda mais força devido à situação atual do país – de luta de povos indígenas e tradicionais em defesa de suas terras e culturas – e também devido às recentes mudanças políticas, em um momento em que tão diferentes visões de sociedade se confrontam.

“É um tema contemporâneo a qualquer momento na história do nosso país. Sempre foi e continuará sendo cada vez mais contemporâneo, em especial com essa recente valorização [do tema, nacional e internacionalmente]. A academia tem prestado muita atenção no tema, e há políticas sendo anunciadas visando a valorização desses povos; para que as línguas nativas não morram e para que as comunidades sejam preservadas”, argumentou.

Problema social silenciado

Mestre em Linguística e fundadora do curso de redação @lumaeponto, a professora Luma Dittrich também não ficou surpreendida com o tema. “Foi exatamente o que esperávamos: um problema social silenciado; um tema-problema que segue a mesma tendência dos últimos anos”, disse ela à Agência Brasil.

Segundo Luma, o nível de dificuldade está, em geral, mais relacionado às habilidades esperadas do candidato do que propriamente com o tema. “O Enem não espera que o candidato demonstre conhecimento sobre o tema, mas sim capacidade de leitura e reflexão. Portanto, os candidatos que entenderam sobre o problema que está dentro do tema e argumentaram refletindo sobre ele se deram bem”, disse.

Estereótipos

A professora Ana Clara enumerou alguns argumentos-chave que podem ajudar nessa dissertação argumentativa. Ela alerta sobre algumas armadilhas que podem diminuir as notas dos candidatos, em especial relacionadas ao uso de estereótipos para se referir a povos ou comunidades tradicionais.

“Pode-se falar sobre reservas, leis de proteção, instituições formadas para garantir a proteção das comunidades. O problema é que, infelizmente, a parte específica da valorização desses povos não é muito abordada para os estudantes em suas rotinas acadêmicas. No caso dos indígenas, sempre vistos como entidade do passado. Nesse sentido, o que é mostrado aos estudantes, desde quando ainda crianças, são formas estigmatizadas, com cocares, bochechas pintadas e um barulhinho feito com tapinhas na boca, algo que ninguém sabe de onde foi tirado, mas que virou som característicos para designá-los”, disse.

Argumentações

“Infelizmente essas populações acabam não sendo vistas como pessoas que usam roupas, estudam, trabalham no cotidiano e estão inseridas na civilidade. São estigmatizadas e apresentadas necessariamente como aquela pessoa na floresta, nua, fazendo rituais. É uma visão muito destorcida que a população, de forma geral, tem e que a escola perpetua direta ou indiretamente. Sem falar nas situações em que, na rotina escolar, a cultura indígena é apresentada de forma generalizada, como se todos fossem iguais, e, por vezes, romantizada”, acrescentou em meio a sugestões sobre como trabalhar o tema.

Professor do curso de redação online Me Salva!, Filipe Vuaden disse que, por abrir possibilidades para a abordagem de diferentes povos e comunidades tradicionais, o tema do Enem deste ano abre um grande leque de argumentações.

“Em termos de dificuldade, é um tema bastante acessível porque abre a possibilidade de o candidato direcionar para diferentes povos ou comunidades tradicionais, como ribeirinhos, quilombolas, pantaneiros, caipiras, sertanejos, o que amplia as possibilidades de o candidato ter alguma referência para mobilizar o texto”, disse ele ao lembrar que a mídia tem noticiado largamente os povos indígenas por conta de serem alvos de conflitos com fazendeiros, madeireiros e grileiros.

Proposta de intervenção

“Há muito o que lembrar na hora da prova e levar para o texto, mas tendo como estratégia principal o domínio das competências de avaliação da prova. É preciso ter ciência de que, em algum momento do texto, é fundamental fazer referência a uma outra área de conhecimento ou disciplina, de forma a ajudar no embasamento da argumentação”, disse.

Vuaden acrescenta ser também aconselhável a apresentação de uma “boa proposta de intervenção para a abordagem que foi dada ao problema”. “No caso, como pensamos em desafios para valorização desses povos e comunidades, o candidato tem de pensar em uma maneira de valorizar ou superar esses desafios. Pode também usar informações históricas, porque desde o período da colonização brasileira os povos tradicionais vêm enfrentando problemas para manterem suas culturas e tradições vivas”.

Borboleta e mariposas

Entre as propostas de intervenção, a professora Ana Clara destaca a busca por representatividade no ambiente político. “Esta é uma questão vital, uma vez que a falta de representatividade é bastante explícita não só na política, mas também em novelas, livros. Sem representatividade, uma borboleta rodeada por mariposas continuará sendo mariposa, como dizia uma poetiza que adoro que é a Rupi Kaur”, argumentou a professora do Corujando.

Competências

Segundo o Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (Inep), o texto apresentado deve ser, em regra, dissertativo-argumentativo. Ou seja, as ideias defendidas precisam estar embasadas por explicações fundamentadas e por argumentações sobre o assunto. Para tanto, é apresentada uma situação-problema, além de textos motivadores, a partir dos quais os conceitos devem ser desenvolvidos, em até 30 linhas.

“As redações são avaliadas de acordo com cinco competências. A nota pode chegar a 1.000 pontos. Por outro lado, há critérios que conferem nota zero, como fuga ao tema, extensão total de até sete linhas, trecho deliberadamente desconectado do tema proposto, não obediência à estrutura dissertativo-argumentativa e desrespeito à seriedade do exame”, informou, em nota, o instituto.

FONTE: Agência Brasil

Oferta de educação bilíngue para surdos deve ser mais ampla, defendem especialistas

Em audiência da subcomissão das pessoas com deficiência, especialistas pediram mais acesso de surdos à educação bilíngue, em que a Língua Brasileira de Sinais (Libras) é oferecida como primeira língua e o português escrito como segunda língua. Essa modalidade pode ser lecionada em escolas e classes bilíngues, escolas comuns ou polos de educação bilíngue e visa atender surdos, surdo-cegos e pessoas com deficiência auditiva sinalizantes.

Fonte: Agência Senado

Palestra – Línguas Invisíveis: Desvelando o multilinguismo nas fronteiras

Palestra – Línguas Invisíveis: Desvelando o multilinguismo nas fronteiras

10/11/2022 16h-18h

Palestrante: Viviane Ferreira Martins 10/11/2022 16h-18h

PALESTRA: LÍNGUAS INVISÍVEIS: DESVELANDO O MULTILINGUISMO NAS FRONTEIRAS

Palestrante: Viviane Ferreira Martins (Un. Complutense de Madrid)

Mediação: Rosângela Morello (IPOL)

Assita online em:

https://www.youtube.com/oeibrasil