Dossiê Especial: Migrações contemporâneas, português língua de acolhimento e políticas linguísticas

Revista Linguagem, Ensino e Educação – Lendu, do curso de Letras da Unesc, acaba de publicar seu mais recente número.

Dossiê Especial: Migrações contemporâneas, português língua de acolhimento e políticas linguísticas, disponível AQUI

Convidamos a navegar no sumário da revista para acessar os artigos!

MPF recomenda que Secretaria de Segurança da PB permita que indígenas tenham nome de etnia em carteira de identidade

Órgão alega que medida é constitucional e assegura concretização de direitos referentes à cultura e identidade dos povos

Indígenas Tabajara. Crédito da foto: Ascom MPF/PB

O Ministério Público Federal (MPF) expediu recomendação à Secretaria de Estado da Segurança e Defesa Social da Paraíba, para que insira informação referente ao pertencimento étnico do indígena, que assim o desejar, no campo “observação” do documento oficial de identificação (RG). Para o MPF, tal medida, além de não encontrar impedimento legal, assegura ao indígena a concretização de direitos referentes à cultura e identidade, a partir da certificação de sua identidade étnica, de modo a reconhecer sua organização social, língua, crença, tradições e costumes.

O procurador Renan Paes Felix justificou na recomendação que a informação referente ao pertencimento étnico do indígena também “é importante para que o Estado tenha em mão o quantitativo de indígenas de cada etnia, de maneira a otimizar a adoção de políticas públicas específicas e de proteção das comunidades indígenas locais”. O membro do MPF ressaltou que “a medida não encontra vedação no ordenamento jurídico, e prestigia aspirações constitucionais, supralegais e legais, o que torna indispensável sua implementação”.

No documento, o procurador da República cita que compete ao Ministério Público Federal a responsabilidade de defender judicialmente os direitos e interesses das populações indígenas. Lembra, também, que a Constituição Federal reconhece aos indígenas sua organização social, costumes, línguas, crenças e tradições. Pontua, ainda, que a Declaração Universal dos Direitos dos Povos Indígenas estabelece que todos têm o direito coletivo e individual de manter e desenvolver suas características e identidades étnicas e culturais distintas, incluindo o direito à autoidentificação.

A recomendação foi expedida a partir de representação do Coletivo Indígena Colmeia. O MPF fixou prazo de 15 dias para que o Estado da Paraíba informe se acata a recomendação e relate as ações e cronograma previstos para seu cumprimento. Ou, por outro lado, apresente justificativa que explique, fundamentadamente, os motivos pelos quais entende não ser possível o cumprimento da medida recomendada.

Procedimento nº 1.24.000.001282/2022-99

Diálogos sobre a Educação reúne autoridades e especialistas em Brasília

Realizado pela OEI no Brasil, evento apresenta dados inéditos sobre a qualidade da educação brasileira, com mais 5 mil questionários aplicados em pesquisa sobre a Primeira Infância; evento será presencial, com transmissão ao vivo pela internet e inscrições podem ser feitas gratuitamente.

Estão abertas as inscrições para a segunda edição do Diálogos sobre a Educação da Organização de Estados Ibero-americanos para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura no Brasil (OEI), que reunirá autoridades, juristas, gestores e especialistas da Educação com o objetivo de discutir os principais desafios da Educação brasileira.

O evento contará com a participação de nomes relevantes como José Henrique Paim, ex-ministro da Educação e atual coordenador da equipe de transição na área da educação; Benjamin Zymler, ministro do Tribunal de Contas da União (TCU); Francisco Gaetani, especialista em Políticas Públicas e Gestão Governamental; Nuno Crato, ex-ministro da Educação de Portugal; Maria Helena Guimarães Castro, Presidente do Conselho Nacional de Educação; Fernanda Castro Marques, do Movimento Colabora Educação; além de outros 30 especialistas na área.

Nos três dias de evento serão discutidos temas como a Educação brasileira oferecida às crianças de zero a 6 anos, com a divulgação dos resultados da pesquisa do projeto “Primeiros Anos”; a relevância do bilinguismo com foco nos idiomas português e espanhol, falados por mais de 800 milhões de pessoas no mundo; e a importância da governança na Educação, com a avaliação de projetos considerados importantes no atual contexto.

As inscrições para participar do Diálogos sobre a Educação – 2ª Edição, promovido pela OEI no Brasil são gratuitas e podem ser feitas no site https://oei.int/pt/escritorios/brasil. O evento também será transmitido ao vivo no canal da organização no YouTube – https://www.youtube.com/oeibrasil .

Funai celebra 55 anos de trajetória na promoção dos direitos indígenas

Foto: Mário Vilela/Funai

No dia em que completa 55 anos de trajetória, a Fundação Nacional do Índio (Funai) reforça o seu compromisso com a proteção e a promoção dos direitos dos indígenas no Brasil. Atualmente, o país tem cerca de 1 milhão de indígenas, que ocupam quase 14% do território nacional. São 305 etnias e 274 línguas faladas de Norte a Sul do país.

Criada por meio da Lei nº 5.371 em 5 de dezembro de 1967, a Fundação é a coordenadora e principal executora da política indigenista do Governo Federal. Atualmente vinculada ao Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública (MJSP), a Funai está presente em todo o país por meio de 39 Coordenações Regionais, 240 Coordenações Técnicas Locais e 11 Frentes de Proteção Etnoambiental.

É papel da Funai promover políticas voltadas ao desenvolvimento sustentável das populações indígenas. Nesse campo, a Fundação promove ações de etnodesenvolvimento, conservação e a recuperação do meio ambiente nas terras indígenas, além de atuar no controle e mitigação de possíveis impactos ambientais decorrentes de interferências externas às terras indígenas.

Compete também ao órgão estabelecer a articulação interinstitucional voltada à garantia do acesso diferenciado aos direitos sociais e de cidadania aos indígenas, por meio do monitoramento das políticas voltadas à seguridade social e educação escolar indígena, bem como promover o fomento e apoio aos processos educativos comunitários tradicionais e de participação e controle social.

Cabe à Funai, ainda, promover estudos de identificação e delimitação, demarcação, regularização fundiária e registro das terras tradicionalmente ocupadas pelos indígenas, além de monitorar e fiscalizar as terras indígenas. A Funai também coordena e implementa as políticas de proteção aos indígenas isolados e recém-contatados.

A atuação da Funai está orientada por diversos princípios, dentre os quais se destaca o reconhecimento da organização social, costumes, línguas, crenças e tradições, buscando o alcance da plena autonomia e autodeterminação dos indígenas no Brasil, contribuindo para a consolidação do Estado democrático e pluriétnico.

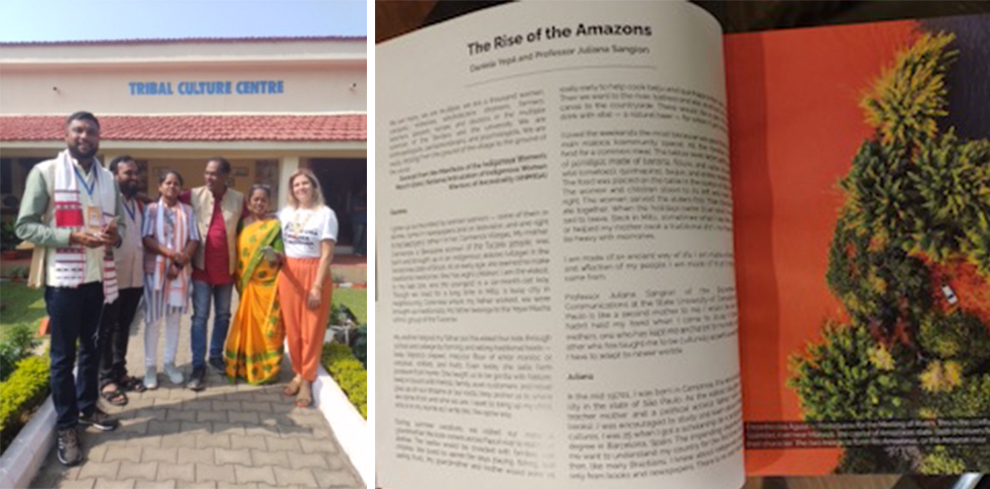

Estudante e jornalista da Unicamp lançam livro na Índia

A estudante do curso de Estudos Literários da Unicamp Daniela (Yepá) Villegas Barbosa e a jornalista Juliana Sangion, que atua na Comissão Permanente para os Vestibulares da Unicamp (Comvest), lançaram, na Índia, o livro intitulado “Still I Rise”, em parceria com outros 30 autores indígenas de diferentes etnias e regiões da Índia. As autoras foram convidadas a integrar a publicação, com um capítulo a respeito da atuação de mulheres que são lideranças indígenas no Brasil, especialmente nas questões de território e da Amazônia, denominado “The Rise of the Amazons”.

Daniela conta que o convite foi feito há alguns meses, depois que as duas participaram de um encontro de povos originários da Índia e de outras partes do mundo, em 2019, denominado Samvaad, que aconteceu na cidade de Jamshedpur. Na ocasião, uma equipe da Unicamp, formada por Daniela, pelo estudante indígena Wallace Krenak e pela jornalista Juliana Sangion, levou ao evento um relato sobre a iniciativa do Vestibular Indígena Unicamp. Daniela e Wallace são da primeira turma de estudantes a ingressarem na universidade por essa modalidade. Juliana, além de atuar na comunicação do vestibular, participou da aplicação da sua primeira edição, na cidade de São Gabriel da Cachoeira (AM), e dirigiu o documentário “Purãga Pesika – Um encontro de boas-vindas”, sobre os primeiros estudantes indígenas a entrarem nos cursos de graduação da Unicamp.

Desde então, o Vestibular Indígena da Unicamp se consolidou como forma de ingresso, tendo passado de 611 candidatos na primeira edição para mais de três mil estudantes inscritos em 2023. No total, cerca de 400 estudantes indígenas de diferentes etnias entraram na Unicamp, em diferentes cursos, nos últimos quatro anos. Desde a edição de 2022, a Unicamp firmou uma parceria com a Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), unificando o vestibular indígena entre as duas instituições.

A estudante e autora Daniela ressaltou a importância de escrever e falar sobre a representatividade de mulheres indígenas, que vem crescendo no Brasil nos últimos anos. “O livro foi uma oportunidade de abordar a diversidade de atuações dessas mulheres indígenas em seus papeis sociais, desde a atuação na comunidade até o ativismo em nível nacional. E tudo isso sem esquecer suas raízes: a ancestralidade, a questão da territorialidade, sua cultura. Toda vez que a mulher indígena estiver ocupando um espaço, ela leva consigo toda sua ancestralidade”, disse.

No capítulo “The Rise of the Amazons”, as autoras abordaram a trajetória de seis mulheres indígenas brasileiras e seu recente papel de relevância no cenário sociopolítico nacional: Sônia Guajajara, Célia Xakriabá, Elizângela Baré, Vanda Witoto, Txai Suruí e Joênia Wapichana. As duas primeiras, inclusive, foram recém-eleitas deputadas, em um feito histórico. Elas compõem a chamada “Bancada do Cocar”, um coletivo de representantes indígenas no legislativo.

Juliana Sangion, que foi à Índia para o lançamento a convite da organização do evento Samvaad, explica que o livro é um projeto em que jovens líderes indígenas, com papel relevante em suas comunidades, relatam suas experiências de impacto para o empoderamento de povos originários. É também um painel de vozes indígenas e não indígenas comprometidas com projetos e movimentos de rupturas positivas. “Foi uma experiência muito enriquecedora trocar informações e ideias com jovens indígenas de um país tão distante do nosso, mas com anseios e potenciais tão parecidos. Falar da iniciativa do Vestibular Unicamp na Índia foi gratificante, na medida em que percebia o interesse e a motivação deles”, disse Juliana.

Segundo Sourav Roy, chefe de responsabilidade social da Fundação Tata Steel, “O livro é nosso esforço para organizar e manter uma coleção de perspectivas e aprendizados de comunidades indígenas para o país e para o mundo em geral, reunida por indivíduos de todo o mundo apaixonados pela identidade tribal. Muitos jovens homens e mulheres que são uma parte essencial do ecossistema Samvaad certamente se inspirarão nesses aprendizados e os integrarão em seus trabalhos e suas vidas, levando-os adiante dentro de suas próprias comunidades”, afirmou.

Samvaad

O Samvaad é principal programa sobre identidade tribal da Fundação “Tata Steel”. É organizado anualmente na cidade de Jamshedpur, sudeste da Índia. Entre os dias 15 e 19 de novembro de 2022, reuniu cerca de 2.500 pessoas de mais de 100 etnias da Índia e de outros países. A partir do tema ‘Reimaginar’, a proposta foi discutir e imaginar o lugar legítimo das comunidades tribais no processo e nos resultados da reimaginação para todo o planeta.

O livro será aberto em uma plataforma digital e traduzido, no próximo ano, para vários idiomas indígenas da Índia e para algumas línguas indígenas brasileiras.

FONTE: Jornal da UNICAMP